If you’re deciding between build vs buy vs integrate, the best answer is rarely “always build” or “always buy.” Use a scorecard to compare time-to-value, differentiation, compliance, data needs, and team capacity—then validate with a small proof-of-value before committing. That approach reduces total cost of ownership (TCO) surprises and avoids integration debt that quietly slows scale. Mastering the build vs buy vs integrate decision is the foundation of scalable systems architecture in 2026.

As companies grow, system decisions shift from being about features to being about constraints: data must be reconciled, workflows must be resilient, and audits must pass on the first try. The tradeoff isn’t just build vs buy—it’s whether you can connect what you already have through systems integration or whether tech stack modernization means replacing the foundation.

The Scaling Problem: Why Systems Decisions Get Harder as You Grow

Early on, a new tool feels like progress: it removes a bottleneck, adds a missing workflow, or makes reporting “good enough.” But as volume, teams, and handoffs increase, every additional tool adds another surface area where data can drift, and processes can break. That’s why “quick fixes” often become chronic operational pain.

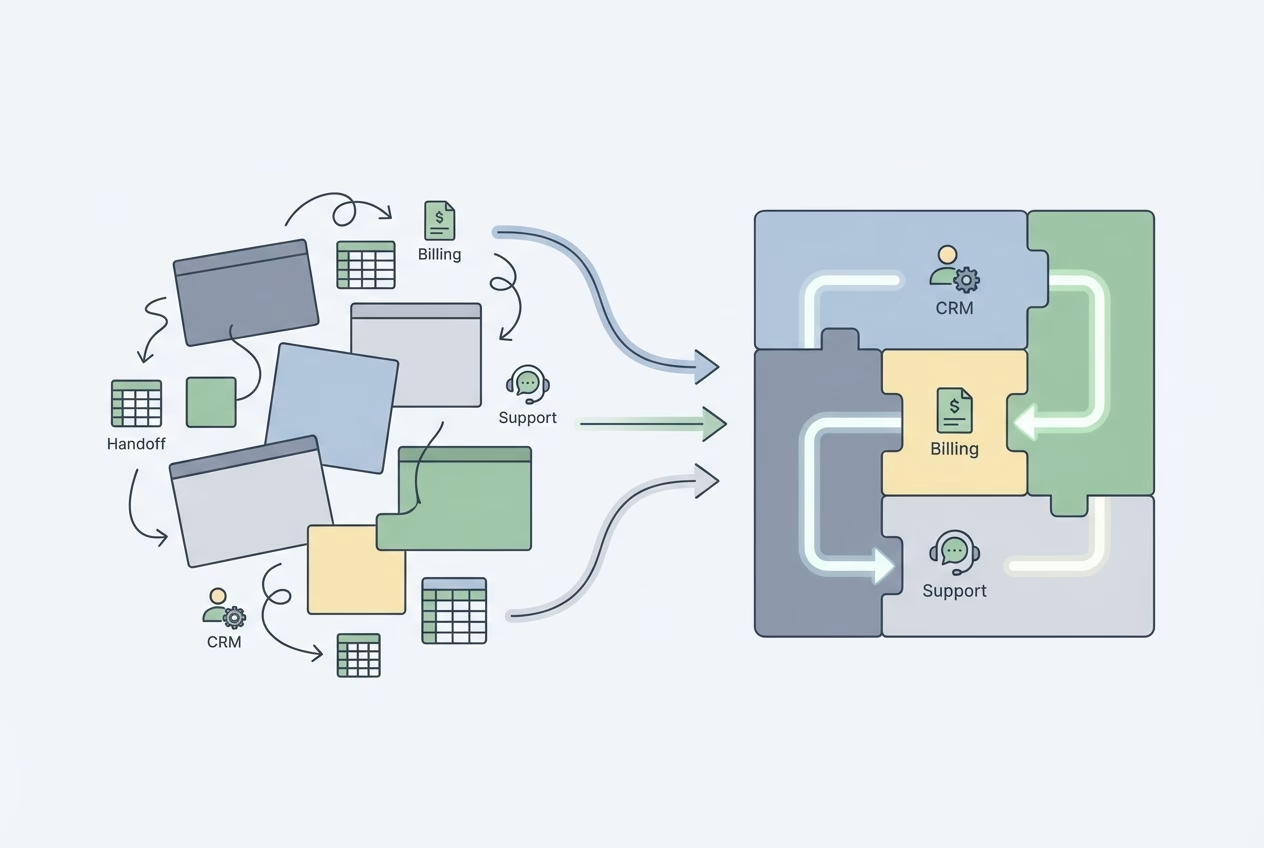

What changes at scale is the cost of inconsistency. A one-off mismatch between billing and CRM might be annoying at 50 customers; at 5,000, it turns into revenue leakage, support backlog, and executive distrust in dashboards. This is the moment when build vs buy vs integrate stops being a product question and becomes a systems design question. That’s why every scaling team eventually faces a deliberate build vs buy vs integrate evaluation.

Common Symptoms (Duplicate Data, Manual Handoffs, Reporting Gaps)

Most scaling teams notice the same pattern: duplicate data across systems, manual handoffs between departments, and reporting gaps that require spreadsheet heroics. The work still gets done, but it depends on tribal knowledge and a few people who “know the quirks.” Over time, those brittle workflows become a hidden dependency for core operations.

Example: A B2B SaaS team uses CRM stages to trigger provisioning, but the actual provisioning happens in a separate internal admin tool. When reps skip a field or update stages out of order, accounts get provisioned incorrectly, and Finance can’t reconcile invoices to entitlements without a manual cleanup sprint.

The Hidden Cost of “Just Add Another Tool”

Adding a tool is easy; operating it is expensive. Each new system introduces onboarding, permissions, data definitions, monitoring, vendor management, and a new failure mode when an API changes or a workflow runs twice. Even when license costs are low, the coordination cost across teams keeps rising.

This is why teams that “only buy” often end up building anyway—usually as scripts, brittle connectors, or ad hoc data pipelines. If you don’t choose an integration strategy intentionally, you still receive one; it’s just the accidental version.

Definitions and Decision Scope (What Counts as Build, Buy, Integrate)

Prior to evaluating options, please ensure they are aligned with the actual decision at hand. “Build” includes more than a full product rewrite, “buy” includes more than an enterprise suite, and “integrate” includes more than a Zapier workflow. Most real-world outcomes are hybrids—and that’s fine as long as the boundaries are clear.

For a clean build vs buy vs integrate evaluation, define the scope at the workflow level (lead-to-cash, ticket-to-resolution, quote-to-renewal), then map the data and control points. Once you know where truth must live and where actions must trigger, you can choose the lightest option that still meets reliability and governance needs.

Build: custom apps, internal services, and data pipelines. Building means you own the logic, the architecture, and the ongoing maintenance. That could be a custom internal app, an internal service in your SaaS architecture, or a data pipeline that standardizes events. Build shines when the workflow is truly differentiating or when compliance requires very specific controls.

Buy SaaS platforms, point solutions, and enterprise suites. Buying means you inherit a mature feature set, a vendor roadmap, and standardized operational patterns. You trade some flexibility for speed and predictability, assuming the tool fits your process and can grow with you. In practice, “buy” still requires implementation, configuration, and change management—especially across RevOps and Finance.

Integrate APIs, iPaaS, middleware, event-driven, and data sync. Integration connects systems so the overall workflow behaves like one coherent platform. That can mean API integration, iPaaS, middleware, event-driven architectures with queues, or scheduled data sync—each with different latency and reliability profiles. Integration is often the most pragmatic choice when the tools are “good enough,” but the handoffs between them are where value is lost.

The build vs buy vs integrate decision framework (scorecard you can use)

A useful framework does two things: it surfaces what matters most to your business, and it makes tradeoffs explicit. Start by scoring each option against the constraints you cannot violate (security, auditability, uptime), then score for acceleration (time-to-value) and leverage (how much it frees your team to focus on the roadmap).

To keep the discussion productive, separate “preference” from “requirement.” If your team prefers a custom UI, but your real requirement is consistent customer data across systems, you may not need to build one. A simple scorecard also helps avoid the common trap where the loudest stakeholder decides the outcome.

| Criteria | Build | Buy | Integrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-to-value | Slower upfront; fastest only if you already have strong internal platform patterns | Fast if requirements match product capabilities and implementation is contained | Often fastest when core tools are acceptable and the bottleneck is handoffs |

| Flexibility & differentiation | Often fastest when core tools are acceptable, and the bottleneck is handoffs | Medium; configuration within vendor constraints | Medium-high; you can orchestrate workflows without rebuilding entire tools |

| Compliance & auditability | Strong if designed well; you own controls and evidence | Strong if vendor meets standards; verify shared responsibility and logging | Varies; requires disciplined governance, logging, and data lineage |

| TCO profile | High initial and ongoing maintenance costs shift to headcount and cloud | Predictable licenses; hidden costs in implementation, training, and add-ons | Moderate; iPaaS/middleware plus internal time and long-term integration upkeep |

| Primary risk | Delivery risk and ongoing ownership risk | Vendor lock-in and fit-to-process risk | Integration debt, silent failures, and an unclear source of truth can pose significant challenges. |

Time-to-Value, Flexibility, Differentiation, Compliance, and Team Capacity

Speed matters, but it’s not just launch speed—it’s “time-to-stable,” meaning the time until the workflow runs reliably without weekly fixes. If your team capacity is thin, building may create a success trap where you ship v1 but can’t sustain v1.1, v1.2, and the operational load that follows.

When you revisit build vs buy vs integrate, ask a sharper question: which option makes the next three quarters easier, not just the next three weeks? Differentiation should be reserved for the workflow that truly moves your competitive needle, not for plumbing work that every company has to do.

Data Requirements: Source of Truth, Latency, Governance, Auditability

Data is where “good enough” systems decisions fail. Decide what system is the source of truth for each entity (customer, subscription, invoice, user, entitlement), what latency is acceptable, and how corrections flow back. Without that, even the best tools produce conflicting numbers that stall decisions.

Integration also changes what “audit-ready” means. If your key calculations are spread across SaaS platforms plus middleware, you’ll need traceability—logs, versioned mappings, and a clear chain of custody for sensitive fields. Those governance requirements may tilt you toward simpler integration patterns or a more centralized data model.

Vendor Risk: Lock-in, Roadmap Alignment, SLA, and Support

Buying and integrating both introduce vendor risk, just in different forms. With “buy,” you depend on the roadmap and packaging; with “integrate,” you depend on API stability, rate limits, and support responsiveness. Either way, confirm SLAs, support tiers, and what happens when your usage doubles.

When done well, this approach makes your decision to build, buy, or integrate reversible rather than permanent. A practical safeguard is to design escape hatches: keep critical business logic in one place, minimize one-off customizations, and document data contracts. Done well, this keeps your build vs buy vs integrate decision reversible instead of existential.

Cost and Risk Comparison (TCO + Risk-Adjusted View)

Teams often compare price tags instead of ownership. A serious total cost of ownership build vs buy vs integrate analysis includes direct spending, internal time, and the cost of failure modes—because downtime and bad data have a real financial impact. When you quantify those, the “cheapest” option frequently changes.

Risk-adjusted TCO matters even more as you scale. If a workflow touches revenue recognition, PII, or customer access, an outage or data defect can trigger churn, refunds, and compliance exposure. That’s why the right build vs buy vs integrate answer is often the one that reduces operational variance, not the one with the lowest monthly bill.

Direct Costs: Licenses, Cloud, Dev, iPaaS, Support

Direct costs are visible: SaaS licenses, implementation fees, cloud spend, and developer time. For integration, include iPaaS or middleware, plus environments, monitoring, and incident response coverage. For building, include engineering, QA, security reviews, and the cost of sustaining on-call quality.

Indirect Costs: Maintenance, Onboarding, Opportunity Cost, Change Management

Indirect costs are where plans break. Maintenance accumulates as integrations multiply, onboarding slows when workflows differ by team, and opportunity cost shows up when engineers are pulled off product work to fix operational gaps. Change management is also a real expense: process redesign, training, documentation, and adoption support.

When you ask, “Is buying always cheaper than building in-house?” The honest answer is “sometimes”—but only when the implementation doesn’t sprawl, and the vendor fits your process. If you buy a tool and then rebuild half of it with custom fields, scripts, and workarounds, you’ve effectively paid to both buy and build.

Risk Model: Outages, Security, Integration Debt, Migration Failure Modes

Risk shifts the recommendation when systems handle sensitive access or regulated data. Building can reduce vendor exposure, but it increases the risk of internal security mistakes if you don’t have mature practices. Integration lowers replatforming risk but can introduce silent failures—especially when error handling and observability are treated as “nice to have.”

In many organizations, the biggest failure mode is a rushed migration that breaks downstream reporting and interrupts operations. If you’re evaluating when to integrate instead of replacing software, consider whether you can prove value by fixing the handoffs first—then replace components only when you can measure the improvement.

Common Patterns and Recommendations by Scenario

Most scaling companies repeat a handful of patterns. The right move depends less on company size and more on whether the workflow is unique, whether the existing tools are structurally broken, and whether the data model can support your future reporting and automation goals.

This phase is also where “integrate” becomes a strategic option rather than a tactical fix. If your platforms are solid but disconnected, integration can unlock scale quickly without the churn and downtime risk of a full replacement. The build vs buy vs integrate choice becomes clearer when you name the exact bottleneck: workflow logic, missing capability, or system-to-system friction. Understanding these patterns makes the build vs buy vs integrate decision faster and more confident.

If the Workflow Is Differentiating: Build (with Integration Boundaries)

Build when the workflow is a competitive advantage, and you need control over the full experience, logic, and data. Still, avoid turning a custom build into a monolith; define integration boundaries so other tools can evolve independently. This keeps custom work focused on value instead of recreating commodity features.

If It’s Standard and Mature: Buy (Then Integrate)

Buy when the category is mature, and your needs align with standard patterns (ticketing, email marketing, HRIS, accounting). The real unlock is what happens next: integrate the purchased system into your operational fabric so downstream teams don’t rely on manual exports. In other words, “buy” usually becomes “buy, then integrate.”

If Systems Are Fine but Disconnected: Integrate (Before Replatform)

Integrate when the business is suffering more from handoffs than from missing features. A targeted systems integration layer can standardize data, orchestrate workflow steps, and improve reporting without asking every team to relearn a new platform. This option is often the fastest path to scale without replatforming, especially in multi-tool B2B environments.

Example: A company likes its billing system and CRM, but struggles with renewals because entitlement updates lag by a day. Instead of replacing both, it adds an event-driven API integration that updates entitlements in near real time and pushes status back to the CRM, shrinking churn risk without a months-long migration. This pragmatic approach often delivers the highest ROI from a thoughtful build vs buy vs integrate choice.

Implementation checklist (avoid integration debt)

Once you choose a direction, implementation details determine whether you get acceleration or a new layer of fragility. Integration debt happens when workflows “work” but aren’t observable, testable, or resilient to change—so every new field or vendor update becomes an incident. A little discipline early preserves speed later.

Even if you picked “buy,” you’re still making architecture choices: where logic lives, how data moves, and what happens when something fails. Treat these decisions like product work, because they will shape your ability to iterate. A well-executed build vs buy vs integrate outcome is one your team can operate confidently six months from now.

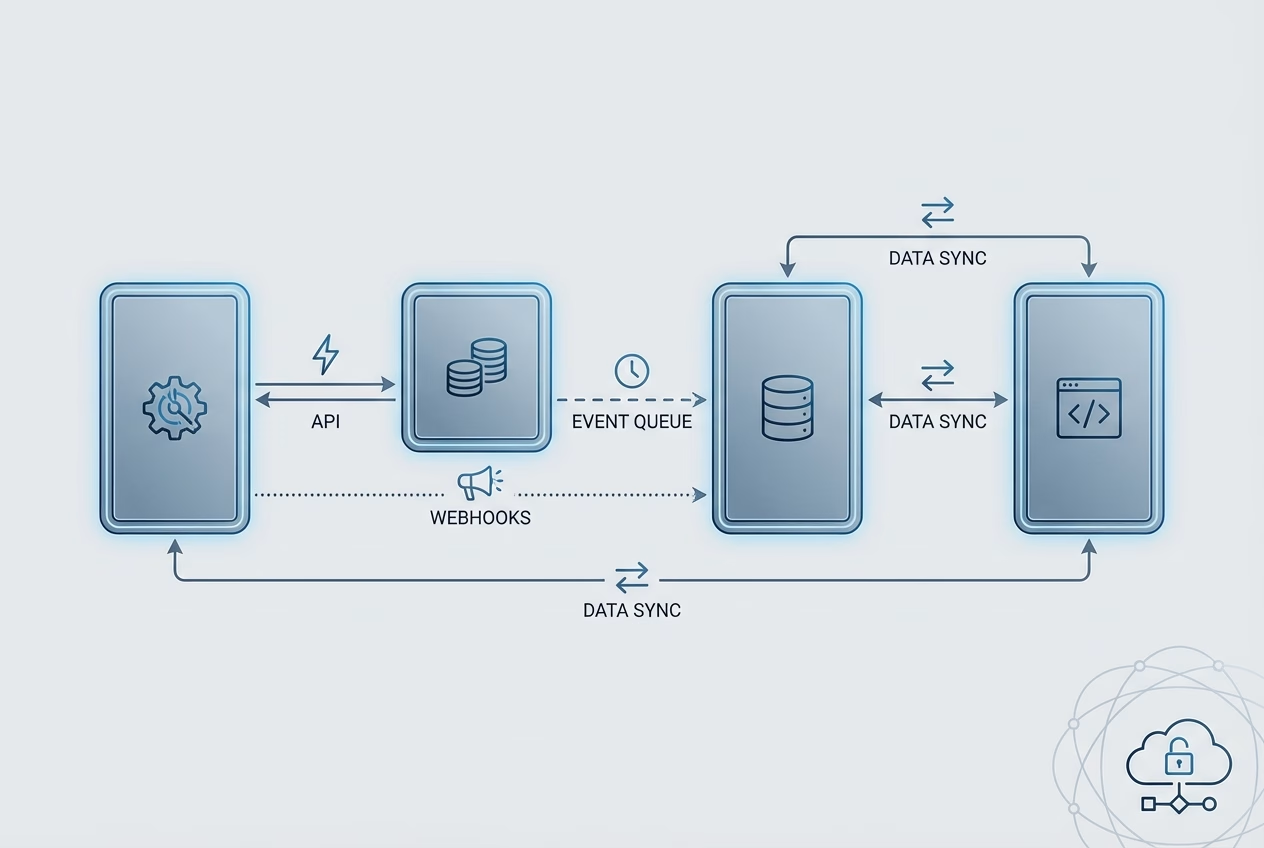

Architecture: APIs, webhooks, queues, versioning, and observability

Choose patterns that match your reliability needs. Webhooks and queues reduce polling and help with scale, but they require strong monitoring; scheduled sync is simpler but can create Architecture: APIs, Webhooks, Queues, Versioning, and Observability

Choose patterns that match your reliability needs. Webhooks and queues reduce polling and help with scale, but they require strong monitoring; scheduled sync is simpler but can create latency and reconciliation work. Whatever you choose, version your integrations and log key events so you can answer, “What happened, when, and why?”

Data: Mapping, Validation, Idempotency, Error Handling, Retries

Data mapping is where most integrations fail quietly. Define schemas, validate inputs, and build idempotency so retries don’t duplicate records or charges. When errors happen, route them to an actionable queue with enough context that non-engineers can triage common issues.

Security: Least Privilege, Secrets Management, PII Controls

Security should be designed in, not bolted on. Use least-privilege scopes for API keys, centralize secrets management, and minimize PII movement between systems. If compliance is a constraint, define logging and retention policies up front so audits don’t turn into emergency projects.

The most reliable teams standardize a few non-negotiables and apply them consistently across projects:

- Document the source of truth for each entity and field that matters for reporting.

- Instrument integrations with alerts for failures, latency spikes, and unexpected volume changes.

- Implement replay-safe processing (idempotency keys or dedupe rules) for all write operations.

- Review permissions quarterly and rotate credentials on a predictable schedule.

Next Steps / CTA

After you decide build vs buy vs integrate, move quickly—but don’t skip validation. The goal is to prove the shortest path to stable outcomes: accurate data, reliable workflows, and a team that can support the system without heroics. A small proof-of-value is the bridge between strategy and execution.

In practice, this means selecting a narrow but meaningful slice of the workflow (one object, one handoff, one report) and treating it as the reference implementation. If the slice meets your requirements for security, uptime, and auditability, you can scale the pattern with confidence.

Use the scorecard to shortlist options, then run a small proof-of-value to validate TCO and time-to-value

A practical 30–60–90-day plan keeps momentum while reducing risk. In the first 30 days, align stakeholders on the scorecard, map data ownership, and confirm non-negotiables like compliance and SLAs. By day 60, implement the proof-of-value with real monitoring and a basic runbook; by day 90, expand the pattern or pivot based on measured TCO, incident rates, and adoption.

If you want a second opinion, bring your current architecture diagram, top three workflow pain points, and a rough estimate of volumes (records/day, API calls, and users). Those inputs make a build vs buy vs integrate recommendation concrete, because they expose where complexity really lives: data, process, or scale.

FAQ

The most common questions we hear revolve around the nuances of build vs buy vs integrate in real-world scenarios:

What’s the difference between “integrate” and “build”? “Build” creates net-new software you own; “integrate” connects existing systems so data and actions flow between them. Integration can include small custom components, but the goal is orchestration rather than replacing whole applications.

Is “buy” always cheaper than building in-house? No—license cost is only one part of TCO. Buying can be cheaper when fit is strong and implementation is controlled, but it can be pricier when heavy customization and ongoing operational overhead pile up.

When should we replace a tool instead of integrating it? Replace when the tool’s core model can’t support your future process (for example, missing critical entities), when the vendor can’t meet security/compliance needs, or when the API and support quality make reliable systems integration unrealistic.

How do we estimate TCO for integrations (iPaaS, middleware, internal time)? Include platform fees (iPaaS/middleware), engineering time to build and test connectors, and ongoing costs for monitoring, incident response, and schema changes. Also, estimate the cost of errors: how often failures occur, how long resolution takes, and which teams are impacted.

What’s the best approach if we need to move fast but have compliance constraints? Choose options that have reliable controls and clear records, and limit the project to a proof-of-value that meets logging, access, and retention needs from the start. Often, the argument points to “buy then integrate” or “integrate” with strict governance and least-privilege access.

How do we decide build vs buy vs integrate for SaaS when teams disagree? Force alignment through a shared scorecard and a measurable pilot. Disagreement usually comes from different definitions of success—once you agree on time-to-stable, data accuracy, and compliance outcomes, the best option becomes more obvious.